Contents

Abstract

Copyright

List of works submitted

Introduction

1 - Consideration of Space in the presentation of EDM

1.1 - Why use large multichannel spatialisation techniques?

1.2 - Why spatial music?

1.3 - Temples for sound spatialisation

1.3.1 - 4DSOUND System

1.3.2 - Dolby Atmos

1.3.3 - SARC - The Sonic Laboratory

1.3.4 - Sound Field Synthesis Methods

1.3.5 - SPIRAL Studio

1.4. - Composition and spatialisation tools

1.4.1 - How do software and hardware tools affect my workflow

1.5 - Spatialisation and EDM: My setup

1.6 - Studio - Binaural Mix

2 - Composition As Performance

2.1 - Music Styles - Techno-House-Trance

2.2 - Composition Overview

2.3 - Compositional Flow

2.4 - Structure: process and intuition

2.5 - Improvisation

2.6 - Conclusion: outlets and dissemination

3 - Performance As Composition

3.1 - A Case Study: GusGus’ performance setup

3.2 - Rethinking Composition as Performance

3.3 - Why 123-128bpm?

3.4 - Physical response

3.5 - Live performance and Musical Flow

3.6 - Methodology for the emerging artists

3.7 - Experimentation with Live Spatialisation

Conclusion

bibliography

Discography

Appendix I

Websites

Abstract

In this commentary I will discuss the technical implementation of sound spatialisation in EDM (electronic dance music) performance practice and outline my compositional approaches involving these techniques. The use of space as a musical parameter in EDM is becoming more common as the accessibility of the technology increases. The technical means of performance and the sonic material combine to create a unique musical aesthetic and listening experience in EDM culture. An historical overview of compositions using spatial considerations as a main musical parameter will situate my work within this artistic practice. Different implementations and propositions of sound spatialisation, as well as the principal locations dedicated to this form of activity will be discussed to contextualise my work. A fundamental part of my research concerns the use of spatialisation tools and techniques to enhance EDM through an immersive sound experience. Concepts and notions of musical ‘flow’ and live improvisation have shaped this research and the compositional and performance aesthetics that have come to underpin my creative practice. Furthermore, the idea of immersivity and the sublime have informed my compositional thinking, and this will be assessed in relation to my objective to create an enhanced listening experience in my live performances. A discussion of the blurred roles of composer/producer/performer will demonstrate how I consider my live performance practice to redefine what a composer of EDM can be. Thus, I consider this research to propose a viable model for modern EDM composers.Copyright Statement

The following notes on copyright and the ownership of intellectual property rights must be included as written below: i. The author of this thesis (including any appendices and/ or schedules to this thesis) owns any copyright in it (the “Copyright”) and s/he has given The University of Huddersfield the right to use such Copyright for any administrative, promotional, educational and/or teaching purposes. ii. Copies of this thesis, either in full or in extracts, may be made only in accordance with the regulations of the University Library. Details of these regulations may be obtained from the Librarian. Details of these regulations may be obtained from the Librarian. This page must form part of any such copies made. iii. The ownership of any patents, designs, trademarks and any and all other intellectual property rights except for the Copyright (the “Intellectual Property Rights”) and any reproductions of copyright works, for example graphs and tables (“Reproductions”), which may be described in this thesis, may not be owned by the author and may be owned by third parties. Such Intellectual Property Rights and Reproductions cannot and must not be made available for use without permission of the owner(s) of the relevant Intellectual Property Rights and/or Reproductions.List of works submitted

Rocket Verstappen (2016-2017 – Live Stereo & Binaural – 8 & 12 minutes)So It Goes (2017 – Stereo & Binaural – 49 minutes)Cyborg Talk (2017 – Stereo & Binaural – 14 minutes)Not The Last One (2017 – Stereo & Binaural – 9 minutes)Chilli & Lime (2017 – Stereo & Binaural – 17 minutes)Stix (2017 – Stereo & Binaural – 13 minutes)Groove Society (2019 – Live Stereo & Live Binaural – 25 minutes)Introduction

When I compose music using spatialisation techniques, I am aiming to create a sense of immersion and movement. I am enthralled by the ability and possibility to move sound in space and I consider it an important feature of music. For me, it enhances the listening experience, and this is achieved through localization, diffusion, height and trajectories of sounds. The implementation of spatial counterpoint in my compositions utilises parallel and contrary spatial motion. This use of spatial counterpoint inherently implies a set of compositional considerations for approaching a new work. My music is different to more typical EDM since we can hear sound trajectories, changeable rates of speed in sonic movement, localization and a height dimension in the sound. I have arrived at a heuristic meaning and common sense sets of rules for spatialisation. This is my spatial counterpointal system for this practice: I have called it ‘gravitational spatialisation’. Essentially it comprises a spectral separation of the audio content with sound positioned according to its frequency.

As a young composer, my first works were created with my own recordings of concrète material “objets sonores” (Schaeffer, 1956, p. 62). These audio files were in a stereo format put into organized sound compositions. The premiere of my first work at an acousmatic concert provided the initial impetus for my discovery of electronic music in space as it was performed over a sound diffusion system which allowed me to spatialise my composition with an orchestra of loudspeakers. This newly acquired awareness expanded my musical horizons; I thought this dimension was to be an important aspect of my future in music. Acousmatic music concerts offered me insightful lessons during my musical progression and the art of diffusion became a prime focus throughout these formative years.

As my thinking and knowledge about working with sound in space developed, the next logical step was to compose works on a surround setup of speakers in order to create pieces containing recorded (fixed) spatialisation, ready for performance. Accessible and intuitive tools to implement and to record spatialisation in my compositions such as OctoGRIS, enabled me to create works for a surround array of eight speakers. This skill of writing sound in space became my preferred mode of expression and creation. I believed the experience of an acousmatic environment was an important and forward thinking musical advancement for the contemporary artist.

I started to go to nightclubs at the age of fourteen years old and I grew up listening to Dance Music, which at the time (around 1988) coincided with the birth of House Music. Over the years, I have acquired knowledge from these music genres by regularly attending events of this kind and I have developed a strong inclination for rhythmical music, especially Electronic Dance Music (EDM). Unfortunately most of them do not utilise the art of spatialisation in any significant way. This is where I thought I could reconcile my musical aspirations: incorporating my skills from acousmatic composition and implement them in an EDM style. I started as an acousmatic composer and I became a composer/performer. I have developed a studio practice, where I want to integrate live performance and in-the-moment decision making at every point. My upbringing in nightclubs was dedicated towards the physical aspect of life. I relate this to my on-going need to experience music viscerally when I compose, and although I had a rigorous training in it, I do not find this sense of physicality in much of the acousmatic repertoire. Since, I have always been drawn to EDM, I started to apply my acousmatic practice to these styles of music production.

In this project, concerning the spatialisation of EDM, the research questions I posited were:

What role can spatialisation play in EDM?

How can I bring acousmatic experience into EDM to enhance it as a performative and compositional genre?

How can creative work merge composition and improvisation?

How can live performance practice redefine what a composer of EDM is?

How do I achieve this through notions of ‘gravitational spatialisation’, immersion and the idea of the sublime?

These questions affect my work as a composer, my role as a performer, and they also influence my sense of flow. Furthermore, this interrogative process made me research the idea of immersivity and the sublime, which have informed my compositional thinking. Through my particular compositional practice, I mix Techno, House and Trance music. I also define how my composer/producer/performer interchangeable roles work seamlessly as it is an interesting creative model. I have explored through the evaluation of spatialisation tools and plugins, which ones would be relevant to implement to EDM.

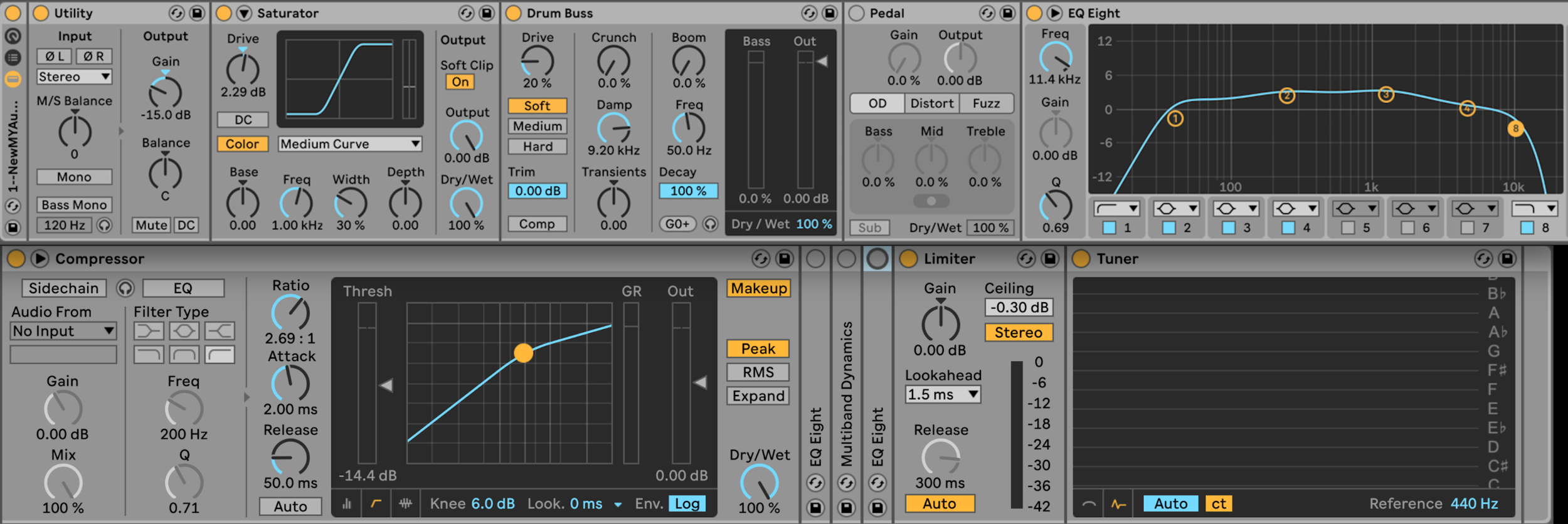

In any discussion of my practice as research, I consider it important to question what differentiates my music from a normal DJ set. Firstly, I regard my works as compositions. They do however, contain long stretches of improvisation and did my acousmatic works. In these earlier works that I created during my undergraduate and Masters study, I would select materials that I thought could work together, and improvise with them in the studio. I would record all of my improvisations and then make a piece with these elements. Essentially, I am doing this now in real time; I create material that form the opening of my piece and through controllers, the Ableton Push 2 and Novation Launchpad Control XL (see Figure 1 below), I improvise with these materials using filtering, reverberation and shuffling effects in order to create a new section of the piece in real time. To demonstrate this creative process, in my piece Stix (2017), at 3’40”, there are sonic transformations occurring on the original materials with heavy filtering, which makes the music nearly disappear until all the loops return with a different rhythm, created by using the shuffling effect. That similarity of practice is important, though I do not do the same thing in every piece. I either have a planned structure for my piece or, I develop my pieces as a logical stream of interlocking ideas that have a forward sense of flow to them. Compositional strategies I employ include applying an identical rhythmic pattern to all the loops, or expanding the sonic space by adding reverb to all the sounds or the speed of movement of these sounds. All of my pieces have a particular set of sonic materials that is unique to them. There is a lot of selection of sonic materials and thinking about space behind my compositions. For instance, Not The Last One (2017) contains mainly sounds similar to pink noise, and this provides a greater cohesion between all the sonic material, especially at 2’23”. My compositional approach is bound to the sense of flow: letting the materials potential steer the form and structure of my pieces.

Figure 1 – Performance setup during Livestream events; Laptop using Ableton Live in conjunction with the Push 2 and the Novation’s Launchpad Control XL, plus an iPad using Launchpad app in order to operate transitions from one piece to another in Live, 2017.

There is a preparation, a selection, and a structure to each of my performances; I organize the set list and program for each specific event. The experimentation is done as the performance evolves, reading and sensing the components of that moment in order to provide the required musical offering:

When an EDM producer (usually also a DJ) in a recording studio selects and organizes sounds in determined ways, he is already acting in accordance with their virtual effects on a dance floor. Experimenting with sound combinations, he is also experimenting with his audience's movements, thus producing a kind of tool that comes from and arrives at his relations with the dance floor (Ferreira, 2008, p. 18).

Thus, there are similarities between the act of DJing and my live performance. They both are organized in advance, but they also allow the freedom to improvise with the already composed musical material. What differs is my ability to decompose and recompose certain parts from the pieces as they unfold. In addition, I can apply specific effects on individual loops, which allows me to generate new musical ideas and directions to develop during the improvisational sections. Although, Pedro Peixoto Ferreira writes that:

This is not to say that there is no experimentation in EDM, only that it is not usually focused on the artistic creation of musical forms but rather on the technological modulation of the sound-movement relation. In other words, EDM is not a kind of creative message sent by a performer to his audience, but the sonorous dimension of a particular collective movement (Ferreira, 2008).

In my work I do consider my method of formal arrangement to be a form of experimentation into what a track or composition can be. I want the experience to be an immersive one that can be appreciated both by the body and the head.

The conception of a website as the ultimate product of this research is a suitable form to transmit and share this project. Therefore, I have built my own webpage to store and share information regarding the progression and development of my music. It is a suitable platform to inform and teach people about music since it reaches our different senses; we can read about music in the form of a text, we can see performances visually, we can hear recording of compositions. All of these digital formats (text, video, sound) are presented on my website with hyperlinks, to gain further insight into the research. The website is a more accessible and involving resource for the propagation of music.

The first chapter of this research concerns the spatial presentation of EDM. I found that spatiality aids the perception and the comprehension of music, and I will explain why I use multichannel spatialisation techniques when I compose. I then contextualize the idea of writing sound in space referencing significant composers and also the theoretical advancements and the technologies related to it. To illustrate the importance and valuable consideration that academic and commercial environments have offered towards spatialisation, I have assessed some important locations and systems that focus on the art of spatial sound. I discuss how software and hardware tools affect my workflow and I will share the performance setup I have developed in order to unite spatialisation and EDM in my work. At the end of this chapter, I contribute some observations on how I create binaural mixes of my compositions for headphone listening.

In the second chapter, I discuss how I consider the act of composing as a performance. My pieces utilise two basic structural methodologies: working with a pre-conceived structure that leads onto a more improvisatory framework or starting with the improvisation itself and then slowly letting the pre-conceived structure emerge from this.

When I consider improvisation in my work, it is set within defined musical boundaries of time and rhythmical patterns. The application of improvisation in my work is limited in its scope, especially if I compare it to a musician such as Evan Parker with his electroacoustic ensemble, who exploits a larger spectrum of sonic and temporal possibilities when playing. He performs without any rules beyond the logic or inclination of his musical state, whereas what I play stays within the EDM genre.

My style of improvisation relates more toward the model of the Big Band era of the 1940s and early 1950s, for instance Benny Goodman or Glenn Miller, which relied more on arrangements that were written or learned by ear and memorized. Thus, my pieces are composed and structured but also include moments where I, as a soloist, improvise within these arrangements. As a Big Band would, I also interpret pieces in individual ways, never playing the same composition in the same manner twice. Depending on the mood, experience, and interaction with the audience, melodies, harmonies, and rhythmical patterns develop and change from one performance to the next.

The idea of rhythm and dancing has been important throughout my life and over several years I attended numerous nightclubs in order to hear DJs during the ‘golden age’ of House and Techno music. The instant somatic gratification from the bass frequencies was compelling. Yet, I was also drawn to the compositional and intellectual aspects of this music. I find a parallel in the writings of Arthur Bissell when he is describing the primary perceptions and expectations of an artist during a performance:

The pleasure … arises from the perception of the artist’s play with forms and conventions which are ingrained as habits of perception both in the artist and his audience. Without such habits … there would be no awareness whatever of the artist’s fulfillment of and subtle departures from established forms … But the pleasure which we derive from style is not an intellectual interest in detecting similarities and difference, but an immediate aesthetic delight in perception which results from the arousal and suspension or fulfillment of expectations which are the products of many previous encounters with works of art (Bissell, 1926, p. viii).

During the first year of this research, I produced some fixed media work that attempted to bridge these different styles of composition: the academic and more commercial music. For me, these pieces lack the sense of physical and intellectual fulfillment that I am looking for when I create work. Consequently, throughout the following experimentations, I concentrated my compositions towards live performance which includes my concept of ‘gravitational spatialisation’, which is a positioning according to the frequency content of my sounds. Furthermore, I realized that sitting down at a concert was not my preferred mode of listening and because I like to move, and I like to hear the sounds moving as well, this form of embodied listening propelled me to search for a new way to perform and experience my music. Ultimately, my objective is to have a self-awareness of what it is I am making musically, where it is drawing from, and to demonstrate that what I am doing is synthesizing those key characteristics into something that is compositionally my own.

One of the things that I have realised while undertaking this research is the idea of multiplicity in my work. As an example, my music cannot be only described as a simple river of musical flow, neither as a massive ocean of music, ultimately my music has characteristics from both. In French, there is a term that describes the natural flow of water that crosses an area of land between a lake, river and ocean; it is called Fleuve. Thus, a Fleuve can be narrow enough to be considered a river and connects to a lake, and it also has the grandeur to reach the ocean. The Amazon River is one of the most important (Fleuve) rivers in the world; it occupies that multiple role of being small enough to be a river but large enough to reach the Atlantic Ocean. Similarly, my music can be pleasing to the ‘outside’ institutions (nightclubs), as well as the ‘inside’ establishment of academic music (universities). It contains hedonistic and visceral sonic qualities, but it can also intellectually stimulate the educated musical ear. The same applies to my compositional methodology: Is my work an improvisation or is it a structured piece? It is actually both; at different times it can change, evolve, progress without boundaries.

My work as a composer-producer is not bound to the studio, and the live performance is not the remix of my music. There is a triangulation (see Figure 2 below), a symbiotic relationship between the studio work, the live performance and the final product (piece) that is essential to my methodology. All of these feed into each other. There is a continuous loop between them, a flow of musical direction going back and forth among them. As such, none of my pieces exist in a final form, they essentially become the sounds of a tool kit. I do not see any distinction between the roles of composer/producer/performer. These are not relevant distinctions for me, as there is a relationship between them that creates the ideal environment for me to make music. This inventive immersion, for me as an artist, is important to engender the creative flow, which has helped me to be prolific over the last two years of this research.

Figure 2 – Triangulation and flow: a symbiotic relationship between the studio work, the live performance and the final product (piece).

The way I compose and perform is through musical structure, process and intuition. The key compositional elements are the gradual accumulation and fragmentation of texturally and rhythmically driven loops. These elements help me to create a sense of musical flow through the ‘emergence’ and ‘disappearance’ of sonic content. The sense of flow is important for me when I compose, create or perform because it is organically evolving, transforming and changing what is happening musically. It allows me to have a vivid awareness, which enables me to react, respond and adapt to the music. It also allows me to reach an elevated state of consciousness in- and of-the-moment.

The concept of creative flow is considered in detail in Chapter Three. I will elaborate on psychologist Mihály Csíkszentmihályi’s theories of ‘flow’ (1990, 1997). In them, he describes ‘flow’ as being in the zone, “in a mental state of operation in which performing is an activity where we are fully immersed in a feeling of energized focus, fully involved, and enjoying the process of the activity” (Csíkszentmihályi, 1990). Thus, I connect his theories to what I am trying to do both musically and aesthetically; not just about the mechanics of it, but also how I want to involve the audience in it. Furthermore, as a composer, I want to integrate concepts of immersivity and viscerality in order to reach the sublime in music.

Among the characteristics that I consider important when composing is the immersive quality of the music. This immersion is related to the enclosed space where an array of speakers is the vehicle to convey the spatialisation and the musical gesture to ‘transport’ the audience during a performance. Ultimately, I want the audience to experience a sense of immersion within the concert space, and through articulation points to make them aware of the musical structure. In addition, viscerality is another concept that is included in my work. It is achieved through immersion, the use of low frequencies and ‘gravitational spatialisation’; it is a phenomenon that emerges from all the actions I take when I perform my music.

One of my musical aims aspire to use an immersive sonic environment to create a three-dimensional audible experience. New media artist and theorist, Frances Dyson (2009), also investigated the significance and implication of immersion in her book Sounding New Media writing that:

The experience of this immaterial, simulated “space” operates through “immersion” – a process or condition whereby the viewer becomes totally enveloped within and transformed by the “virtual environment.” Space acts as a pivotal element in this rhetorical architecture, since it provides a bridge between real and mythic spaces, such as the space of the screen, the space of the imagination, cosmic space, and literal, three-dimensional physical space. Space implies the possibility of immersion, habitation, and phenomenal plenitude (Dyson, 2009, p. 1)

Her notion of immersivity, however, is more related to the immaterial, intangible dimension of life, which is quite opposite to my desire to ‘touch’ viscerally (almost physically) the listener with my music.

When I perform live EDM, I want to achieve greater expression in my work rather than offering a passive acousmatic sound diffusion. Additionally, a way to accomplish the expressive sublime in my music is through the idea of immersion. The concept of immersion within my work is produced in the studio and it becomes a reality during the performance when using an array of speakers that surrounds the audience. Composer Simon Emmerson (2007), elaborates on ideas of new spaces and perspectives in regards of immersivity in a live performance:

Two new kinds of listening spaces relying on technology for their sound systems emerged from the 1960s to the 1990s. Both are totally immersive, but one is large and public, the other small and private. First the spaces of leisure listening, increasingly with the participation of dance, group encouraging and inclusive; secondly the space of the ‘personal stereo’, individual and exclusive. […] The image is here totally immersive, designed to envelope, to create a total space into which intrusion of extraneous sound is impossible, not because it is excluded but because it is masked. The image is close, surrounding and omnidirectional, possessing a kind of amniotic reassurance (Emmerson, 2007, p. 103).

Immersivity has multiple theoretical aspects that are explored by Emmerson (2007), but for me it is really about being surrounded by sound. There is not one sonic point of origin, the listener/dancer is in the middle of it (the speaker setup) and the central position (sweet spot) is not important since people are moving and changing positions while they are dancing. For me, immersivity is where the body is engulfed in an overwhelming feeling of sonic presence. I concur with Emmerson’s idea of the performance space being the ultimate listening environment: “These spaces were always there […] but have now become more fully integrated into the ‘total’ experience” (Emmerson, 2007, p. 116).

I compose my music in a particular kind of way, where I use a certain type of reverb to give an artificial sense of distance. I work with the sense of length and scale, and I use multiple speakers to create that sense of immersion in that live space. It is not an imaginary landscape, but it is leading to the idea of the sublime in music, where I am imagining something that is physically imposing. When composing, I envision my music playing in a massive warehouse, crowded with people, with the sound coming from all around me. Part of the musical experience is when we let our ego depart from reality, not thinking about trying to imagine things but to be immersed in the physical sensation of the music and the sonic qualities ‘in-the-moment’ that are giving pleasure. In my music, I am trying to conjure something that is large scale and monumental, that is beyond human scope in order to create the idea of the musically sublime. I am doing this through playing with high volume, a wide frequency spectrum and a large number of loudspeakers in order to reach the intended sonic result.

One of the most important aspects of what I am doing is creating a sense of the sublime both for me as a composer/performer and the audience. The definition of the sublime that I am using is finding roots in classical antiquity, specifically in the influential first-century Hellenistic treatise the Peri Hupsous, attributed to Dionysius Longinus (Gilman, 2009, p. 533). Longinus concerns himself with the emotive force of the sublime as a moral agent, as a persuasive power to move and better the mind.

In my compositional quest, there is always this consideration to create, for me and the audience, something that is almost awe inspiring, as with the idea of the sublime. I am not aiming to make nice landscapes that are beautiful, I am endeavoring to create epic mountains, hence oriented towards the concept of the sublime. This is the aesthetic intent of my music; to be massive, impactful, almost symphonic in scale. I want to take the audience on a journey, not a physical or mental one but an emotional sublime experience.

The idea of the sublime in my music refers more to philosophical aesthetics than to solely musical terms. The notion of the sublime I refer to is Kantian in nature (2007, p. 51): like having vertigo, like teetering on the edge, where the ego disappears. It is the idea that people are involved in an experience in which they get carried along with the flow of the music that I am creating, to such an extent that their own ego, and their own perception of the music becomes less important, they are immersed in this experience where they become one as a whole collective.

In my music, there are powerful and visceral - somatic (bodily) booming sounds, not simply a pleasurable (beautiful) sonic content, it relates to the idea of the sublime in the philosophy of art. In aesthetic theory, “a more classical conception of beauty might claim that something is beautiful because it is a correct and coherent arrangement of parts into a whole” (Beauty, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy[1]). A piece of music is beautiful because all of the element within it fit together creating a perceived sense of good balance and continuation or flow to form something pleasurable. Unlike the beautiful, the sublime is impressive and awe inspiring.

The sublime usually includes the impression of an object which can be fearful but does not inspire fear at that moment. Philosopher Immanuel Kant conceived of the sublime as “the power of reason over nature” (Kant, 2007, p. 51). His description of the dynamic sublime falls in line with Edmund Burke’s conception; “it is the ability of reason to overcome the feeling of fear that we get from seeing something which can be dangerous but poses no current danger” (Burke, 1958, p. 69). For example, Anton Hansch’s painting (see Figure 3 below) of a majestic mountain range, is connected to the idea of sublime inspired awe and even terror due to its vastness and power, but because we are distant from that potential danger and we are in a safe place, we can then appreciate the grandeur of it and the feeling of the sublime.

Figure 3 – Anton Hansch’s painting of the big three mountains of Eiger, Mönch, and Jungfrau, part of the Swiss Alps (1857).

Thus, the beautiful elicits positive responses or emotions to sounds, while the sublime manifests unease or distress often followed by pleasure having realised that the sounds are not something which pose an immediate danger. My composition So It Goes (2017) includes instances of sonic intensity (at 22’22” and 23’18”), where the musical climaxes can sometime sound powerful and be overwhelmingly intense but there will be a release of sonic activity and a return to calmer moments. This musical crescendo and decrescendo connects to the idea of the sublime; facing the exhilaration of reaching peaks without falling off the cliffs, or the fear of stumbling down deeper into the valleys.

My work plays with these ideas of sonic puissance but also, it offers peaceful and exquisite musical transitions in order to reach the sublime. This is echoed in Kiene Brillenburg Wurth’s thesis on The Musically Sublime (2002):

It is to say that the particular structure of Kantian sublime experience parallels the structure of the process of sublimation in so far as a ‘negative’ feeling of frustration or terror (pain) is removed and transformed into a ‘positive’ feeling of delight or elevation (pleasure). What happens in the Kantian sublime, I will explain, is that an initial, apparently unacceptable awareness of self-limitation (manifested as frustration or terror) is resolved – removed and sublimated – into a delightful, psychologically more welcome, realization of one’s own supersensible power and limitlessness. In the end, the Kantian sublime experience is thus never truly disturbing but rather reassuring: any feeling of helplessness, frustration, or fear, any self-undermining sensation, in all its negativity, promises (if not already implies) a positive ‘result’ of self-affirmation and self-elevation exorcising that very frustration or fear (Brillenburg, 2002, p. xx).

Additionally, the sublime in my music is achieved through the ‘flow’ that provides the extension and duration for my piece to get longer, as with stream of consciousness. Traditional musical syntax is almost overturned; the sense of musical timing is very much extended; my tracks last between 15-20 minutes. My compositional process is not simply short piece after short piece, it has long flowing, almost symphonic lines of sounds, perhaps being lost musically, structurally within that. In this approach, we are carried along as a listener on the surface of the music, but the understanding of the musical structure is practically impossible to perceive because of the length, of the changes and transformations that occur, and also because the musical phrases are continually developing or evolving. My music is not structured like a conventional EDM track, or a verse and chorus pop format in which the listener can more easily orient themselves. There are musical materials that do come back, but they do so in an organic manner. This organic quality lends itself to achieve the sublime as there is a sense of order but it cannot simply be predicted by the listener.

My compositions relate to an idea developed by Adam Krims (2000) regarding a sublime musical aesthetic, where “the result is that no pitch combination may form conventionally representable relationships with the others; musical layers pile up, defying aural representability for musically socialized Western listeners” (Krims, 2000, p. 68). According to his article, the idea can be described as the “hip-hop sublime”. Thus, following Krim´s representation of this musical style I suggest a “techno sublime”, where it connects with the reality of its environment; in desolate and underground warehouses, which also suggest a figure for inner-city life that describes a post-industrial urban devastation.

We are reminded of Edmund Burke´s formulation of the sublime. Burke goes on to describe the fear of being smashed by “unfigurable” power. [Techno sublime´s] representation situates the listener in the geographical and social location from which capital´s smashing power is most visible. In other words, [the Techno sublime] presents a view from [the destitute post-industrial rave parties] at the massive, unfigurable but menacing force of world capital (Krims, 2000, p. 72).

Conceptually, I relate my work to that of musician Jon Hopkins. In his piece Collider (2013), he plays with the sense of timing and change; it is not focusing on simple harmonies that slowly evolve, the layers do not coincide, and the harmonic layers grate against each other in order to produce a sense of inner rhythmic instability. These musical elements create a certain musical (physical) unease or disturbance that relates to this idea of the sublime in music.

The feel-good quality to my music can be interpreted as superficial (pleasant to the ears) but there is an intellectual questioning regarding what comes next in order to provide this musical continuum. The objective when I compose/perform is to feed into what sounds good to me and into different models of musical decision-making. The inter-relationships between the fast-paced rhythmic loops from my pieces mixed with the longer, reverberating sounds are playing with the concept of ebbing water; transitioning smoothly or not with current and new sonic materials. This methodology of composing is reflected in my music and is described in Jacques Attali’s book Noise:

[Music] is more than an object of study: it is a way of perceiving the world. A tool of understanding. […] Music, the organization of noise, is one such form. It reflects the manufacture of society; it constitutes the audible waveband of the vibrations and signs that make up society (Attali, 1976, p. 4).

In my research into the application of spatial technologies and techniques to EDM, in order to create immersive and sublime experiences, this is one way in which I use music to understand my place as an original creative person within society. The music is more than an object of study and technical implementation of compositional principles, it is a way for me to articulate how I express myself in the world.

1 - Consideration of Space in the presentation of EDM

The fundamental research question underpinning this portfolio is how can real-time spatialisation be used in Electronic Dance Music (EDM), specifically in the context of live performance? I believe the 3D presentation of sound can enhance the visceral qualities of music through a more immersive sound experience. Although we are used to cinematic surround (Dolby 5.1/7.1), surround sound has been little used in EDM. There are a wide array of techniques and tools available for spatial composition, from IRCAM’s SPAT (Spatialisateur), OctoGRIS, Ambisonics to the 4DSOUND system. I will evaluate these technologies and examine how such techniques are incorporated into my compositional methodology.

An historical overview of composers who have used spatial techniques and the often-bespoke places or systems they have created for, will allow me to situate my compositions within this artistic practice. The different implementations of spatialisation methods that have been used (as well as the principal locations dedicated to this form of activity) will be interrogated. In addition, I will focus on how spatial techniques are integral to my creative practice. I will demonstrate that, with better access to powerful, yet simple and efficient technologies, spatialisation in EDM can enhance the listening experience.

1.1 - Why use large multichannel spatialisation techniques?

Ludger Brümmer writes that, “Spatiality in music is more than a parameter for the realisation of aesthetic concepts. Spatiality aids in the presentation, the perception, and the comprehension of music” (Brümmer, 2016). Regarding the research he conducted at the Zentrum fur Kunst und Medientechnologie (ZKM), Brümmer goes on to state that:

Human hearing is capable of simultaneously perceiving several independently moving objects or detecting groups of a large number of static sound sources and following changes within them. Spatial positioning is thus well-suited for compositional use (Brümmer, 2016, p. 2).

Throughout my research, the spatial location of sounds is not used to convey a meaningful structure. Despite Brummer’s contention above, from my working in spatial sound, I contend that any more than four layers of sonic movement cannot be accurately perceived and recalled. This means that the integration of space as a structural parameter needs to be carefully controlled. What interests me about the combining of multiple spatial trajectories is how they coalesce in a three-dimensional space to provide a sense of immersivity and viscerality.

The sense of immersivity through the use of spatialisation arises from “the fact that human hearing is capable of perceiving more information when it is distributed in space than when it is only slightly spatially dispersed” (Brümmer, 2016, p. 2). It is a phenomenon where sounds are capable of concealing or masking each other (Bregman, 1990, p. 320).

1.2 - Why spatial music?

In my work, spatialisation is an important dimension of the music; it provides a dynamism and physicality that enhances the auditory experience. Regarding the attribution of value to space in my music, there is an integration of spatialisation with a developmental sense of how the track unfolds, it is a meaningful part of how I structure my pieces. Space is actually used as a structural element. Spatialisation enables me to think about critical compositional decisions; do I keep one or more sonic elements moving in space or should I keep it static, should I reduce the immersive environment by thinning the texture down, etc. Also, it allows me to build my piece towards a certain type of energy. One important element of spatialisation for me is in the articulation of form. A trajectory is not always of structural importance but what is significant is the amount of spatialisation, where the density of spatial movement creates a more or less immersive sense. Depending on the context, the reduction of spatialisation is necessary in a moment of repose or for the beginning of a build-up. Adding layers of movement with the spatialisation, as a result, becoming more complex, enables me to articulate form through the emergence and disappearance of sonic elements.

The significance of spatialisation in my work varies; it is to some extent present all of the time but in varying degrees of importance. It is always present and perceptible. It is not an add-on effect which is how Steve Lawler used it when I attended his performance with the Dolby Atmos system at Ministry of Sound in London (August 19th, 2019). (https://www.decodedmagazine.com/steve-lawler-atmos/). My spatialisation can highlight a specific sonic element or it can emerge and disappear during an intense musical section because at certain moment the rhythm is the current important musical parameter. In my performance practice, the space behaviours are pre-set (depending on their frequency content, each loop has a fixed role attributed in space), and I fade them in and out. During a performance, I do not improvise with spatial movement and I do not create holes within this spatialisation; I always try to create a holistic immersive environment.

In my experimentations with space, I relate to Mexican band leader Juan García Esquivel and how he must have felt at the time when he used the potential of the stereo image on his recording (Exploring New Sounds in Hi-Fi/Stereo (May 1959, RCA Victor) in order to create new listening experiences. I have developed diverse types of spatialisation which I consider effective in my music. I have developed, and continue to develop a working method for spatialisation in EDM. It is dance music on its own term of what I can do. It is establishing a new outlook for the contemporary EDM producers. What I am doing has significance, interest and value by itself. Thus, I suggest that we are at the point of establishing a new era of spatialisation for EDM.

There is much valuable research about “spatialisation and meaning”, and how it creates a narrative of space. My research can be akin to Ruth Dockwray and Allan Moore’s (2000) article about sonic placement in the “Sound-box”, where I discuss localization and movement of sounds in my “Dome-box” (within the SPIRAL Studio).

From the outset of electronic music, the earliest practitioners investigated the spatial presentation of this new genre, particularly in a performance context. “Spatialisation has been an important element in classical electronic music, showing up in work by Karlheinz Stockhausen, Luciano Berio, Luigi Nono, John Chowning, and many others. A mainstream practice emerged in which spatialisation consisted of the simulation of static and/or moving sound sources” (Puckette, 2017, p. 130). Of the composers who have used spatialisation in commercial projects, Amon Tobin is one of the most prominent. His album Foley Room was performed at the GRM over the acousmonium in multi- channels format. He also scored for video games and he commented about his surround mix for the soundtrack of Tom Clancy’s Splinter Cell: Chaos Theory (2005):

The reason it was easier than a stereo mix is because you have a lot more physical room to spread out all the different sounds and frequencies. So, the issue of sounds clashing and frequencies absorbing all the frequency range in the speakers is a lot smaller when you've got that much more room to play with (Tobin, 2005)[2].

Several commercial electronic artists also considered space in their CD/DVD releases. In 2005, Birmingham based Audio-Visual collective Modulate produced a multichannel project which allowed a 5.1 playback at home (Modulate 5.1 DVD)[3]. The electronic music duo Autechre, consisting of Rob Brown and Sean Booth, explained their use of space in the stereo field when working on the album Quaristice (2008):

If we’re using effects that are designed to generate reverbs or echoes the listener is going to perceive certain sized spaces, so you can sort of dynamically evolve these shapes and sounds to actually evoke internal spaces or scales of things’. […] You can play with it way beyond music and notes and scales. (Brown quoted in Ramsey, 2013, p.26)[4]

When composing music for a multichannel system, adding movement and localisation opens new possibilities for musical expression and listening experience. Such systems provide a multitude of listening positions, which offer new ways of listening to music. These modes of listening cohere with music theorist Ola Stockfelt’s invitation to develop and cultivate, in our modern life, a variety of modes of listening:

To listen adequately hence does not mean any particular, better, or “more musical”, “more intellectual, or “culturally superior” way of listening. It means that one masters and develops the ability to listen for what is relevant to the genre in the music, for what is adequate to understanding according to the specific genre’s comprehensible context […] we must develop our competence reflexively to control the use of, and the shifts between, different modes of listening to different types of sounds events (Stockfelt, 1989, p. 91).

In his PhD thesis entitled The Composition and Performance of Spatial Music, Enda Bates observed that, “the study of the aesthetics of spatial music and the musical use of space as a musical parameter therefore appears to be a good way to indirectly approach electroacoustic music composition and the performance of electronic music in general” (Bates, 2009, p. 5). Furthermore, he adds “spatial music is in many respects a microcosm of electroacoustic music, which can refer to many of the different styles within this aesthetic but is not tied to any one in particular” (Bates, 2009, p. 5).

Concerning the validity of spatialisation, I have found analogous opinions to mine in Ben Ramsey’s research, where he stated: “this idea of using space as a compositional narrative is a complete departure from more commercial dance music composition practice, and very much enters the realm of acousmatic music, where space and spatialisation is often considered part of the musical discourse for a piece” (Ramsey, 2013, p. 17). This also relates to Denis Smalley’s approach to acousmatic composition and his concept of spatiomorphology:

And I invented the term ‘spatiomorphology’ to highlight, conceptually, the special concentration on spatial properties afforded by acousmatic music, stating that space, formed through spectromorphological activity, becomes a new type of source bonding (Smalley, 2007, p. 53).

Stefan Robbers from Eevo Lute Muzique has engineered a performative sound system called the Multi Angle Sound Engine (MASE). It offers the DJ/performer a multichannel diffusion system which allows to play with space on a stereo system:

The MASE interface offers DJs or producers eight independent audio inputs and a library of sound movements. The user has ample options for assigning a trajectory to an incoming audio signal and to start, stop or localise this. Specially designed software allows users to programme and store their own motion trajectories. The system is space-independent, users can input the dimensions and shape of a room and the number of speakers which are to be controlled (Evo Lute Muzique quoted in Ramsey, 2013, online)[5].

The ideas behind the MASE system and the compositional territory it offers, opens up a way to incorporate commercial dance music with “the more experimental and aurally challenging compositional structures and sound sources that are found in acousmatic music” (Ramsey, 2013).

Another artist that embraced new technologies in order to compose music in 3D is Joel Zimmerman (aka Deadmau5). In 2017, he converted his production studio to be fully compatible and compliant with Dolby Atmos systems. “Deadmau5 even says that he’ll produce all his new songs first in Atmos to give them the most three-dimensional sound, and then “submix” down to stereo after for more common systems and listening” (Meadow, 2018).

1.3 - Temples for sound spatialisation

A variety of 3D sound projects are currently finding their way into the world of nightclubs and EDM culture more widely, demonstrating a steady and growing interest in spaces with sound spatialisation. These environments, both academic and commercial, provide a place to experiment with spatial audio and this could be seen as part of a broader shift towards more public venues and experimental performance spaces valuing immersive, 3D audio experiences.

1.3.1 - 4DSOUND System

Figure 4 - 4DSOUND system (Image by Georg Schroll via Compfight), 2015.

The software for the 4DSOUND system (see Figure 4 above) is coded in Max4Live (a joint project between Cycling74 (Max) and Ableton (Live). The founder Paul Oomen explains that “the hardware comprises an array of 57 omni-directional speakers – 16 pillars holding three each, as well as nine sub woofers beneath the floor. By carefully controlling the amount of each sound going to each speaker, it is possible to localise it, change its size, and move it in all directions” (Oomen, 2016).

In February 2016, I attended 4DSOUND’s second edition of the Spatial Sound Hacklab at ZKM in Karlsruhe, Germany, as part of ‘Performing Sound, Playing Technology’[6], a festival of contemporary musical instruments and interfaces. During four intensive days, creators, coders and performers experimented with new performance tools, a variety of instrumental approaches and different conceptual frameworks in order to write sound in space. The founder Paul Oomen believes that “spatial awareness and how we understand space through sound plays an integral role in the development of our cognitive capacities” (Oomen, 2016). As a result, he considers that “there will be new ways to discover how we can express ourselves musically through space, and our understanding of the nature of space itself will evolve” (Oomen, 2016). He also writes that:

Spatiality of sound is among the finest and most subtle levels of information we are able to perceive. Both powerful and vulnerable, we can be completely immersed in it, it can evoke entire new worlds – if we are only able to listen. After eight years of developing the technology and exploring its expressive possibilities, it has become clear that the development of the listener itself, the evolution of our cognitive capacities, is an integral part of the technology.

Spatial sound is a medium that can open the gate to our consciousness, encouraging heightened awareness of environment, a deeper sense of the connection between mind and body, empathic sensitivity and more nuanced social interaction with those around us. It challenges us to listen to the world in a more engaging way, offering us a chance to become more sensitive human beings (Oomen, 2016)[7].

According to its founder, “central to 4DSOUND’s plan for the project is to establish a laboratory for artists, thinkers and scientists to explore ideas about space through sound, and create a platform for cross-fertilization of different fields of knowledge to further the development of the medium” (Oomen, 2016). The lab also allows for a new form of spatial listening: in enabling the refinement of conscious listening practice, increasing awareness of surroundings and exploration of a deeper connection to the self and others. Paul Oomen (2016) hopes to “encourage a change in the quality of our everyday experience” through the 4DSOUND system. Oomen writes:

We are committed to engendering a new ecology of listening, improving the sound within and of our environments and expanding our ability to listen. I think this is a movement that will really begin to take shape over the coming years as we evaluate many aspects of modern life, of our shared environments, and our understanding of sound in influencing this (Oomen, 2016)[8].

Figure 5 - 4DSOUND’s second edition of ‘Spatial Sound Hacklab’ at ZKM in Germany, 2016.

From my presence at the hacklab, I was able to experience the qualities of the 4DSOUND system and perceive its potential for diffusing music in space (see Figure 5 above). I was able to interview many of the participants. Ondřej Mikula (aka Aid Kid), a composer from the Czech Republic, stated that, “these systems of spatial audio (4DSOUND and Ministry of Sound’s Dolby Atmos) are the future of electronic music.” Furthermore, he mentioned that:

When you have this much space, you can really achieve a ‘clean’ sound because of the mix. When the frequencies are crushing in your stereo mix, you can only put the sounds on the side [or the middle] or using the ‘side-chain’ effect [in order to create frequency space in your mix]. But when you have this full room [of space] you don’t have to worry [about clashing frequencies], you just put the sounds somewhere else. I have lots of [sound] layers in my music (the way I compose) and it handles all of them (numbers of layers) without cutting the frequencies. This is a big advantage for me [when I compose]. (Mikula, 2016)[9]

On site at the ZKM, I interviewed the French composer, Hervé Birolini, who commented that:

Spatialisation [in my work] is fundamental. I conceive myself to be a stage director of space, in a close manner of the theatrical term. […] It appears to me more and more like something extremely natural [to include spatialisation when I compose]. It is so natural that for every situation that I have been proposed to participate [and to compose sound], like for stage music, a ‘classic’ electroacoustic music, a work for the radio or else… I will adapt the piece [of music] and its spatialisation to the space that I wish to create (Birolini, 2016)[10].

He added that his experience was unique and offered efficacious results when playing with space on the 4DSOUND system:

In order to create a sense of realism in music, I had the possibility of ‘exercising’ the elevation (sense of height). Although more complex to integrate in a work, it can enhance the surround environment in electroacoustic music. Thus, 4DSOUND is ‘Space’ in all of its dimensions; in front, behind, at the sides, above and below us. I can say that this system is unique, I’ve had the experience to experiment with several [diffusion] systems [around the world] and this one can’t be heard anywhere else. Furthermore, it [the 4DSOUND] operates ‘naturally’ and efficiently (Birolini, 2016)[11].

Some well-known commercial artists have been able to use and perform with the 4DSOUND system including Max Cooper and Murcof. Max Cooper is a DJ and producer from London, whose work exists in the intersection between dance floor experimentation, fine-art sound design, and examination of the scientific world through visuals. Murcof is the performing and recording name of Mexican electronica artist Fernando Corona. Murcof’s work with the 4DSOUND system has allowed him to expand and develop his method for structuring narrative and composition with spatialisation: “The system really demands to be heard before writing down any ideas for it, and it also pushes you to change your approach to the whole composition process” (Murcof, 2014)[12]. Max Cooper has acknowledged that: “The 4DSOUND system, and a lot of the work I do with my music in terms of spatiality and trying to create immersive spaces and structures within them, has to do with psycho-acoustics and the power of sound to create our perception of the reality we’re in” (Cooper, 2017)[13].

This unique sound experience is technically fascinating and leaves us with a great spatial sound impression. One of the sonic characteristics that I found convincing with this system is the realistic and perceptible sense of height, providing a coherent 3D sound image and listening experience. However, the system requires two trucks to transport all of the equipment, which makes it expensive to stage a 4DSOUND show, and each is a one-off experience and therefore although highly attractive as a format. Furthermore, it is not appropriate to my current research, which aims to utilise commercially available tools in a highly versatile yet portable system that can be performed with Live.

1.3.2 - Dolby Atmos

Figure 6 - London’s Ministry of Sound collaborates with Dolby Laboratories to bring Dolby Atmos sound technology to dance music. Photo credit: unnamed, Found at www.mondodr.com, 2016.

Another system for the spatial presentation of Electronic Dance Music is the newly installed Dolby Atmos technology at London’s Ministry of Sound club (see Figure 6 above). The partnership between Dolby and Ministry of Sound gave rise to an important innovation in the performance of EDM in clubs, allowing music to be spatialised on the vertical as well as on the horizontal level. Matthew Francey, managing editor for Ministry of Sound’s website, wrote: “For the listener, this means that sound can appear anywhere along the left-to-right and front-to-back axes, and also at different heights within the audio field” (Francey, 2016)[14]. What makes the Dolby Atmos system an interesting solution is that it does not require a specific number of speakers for the spatialisation to function. In a classic Dolby Digital 5.1 mix, sounds are assigned to a specific speaker, so if you want a sound to come from behind the listener on the right, you would pan it to the rear right channel. Mark Walton, music journalist, states that:

With Atmos, sounds are "object based", meaning that the sound is given a specific XYZ coordinate [like Ambisonics] within a 3D space, and the system figures out which speaker array to send the sounds through, no matter how many (up to 64) or few (as low as two) there are. Even when the sound is panned, you move it through each individual speaker in the path, creating an immersive experience (Walton, 2016)[15].

Figure 7 - Prior to the Ministry Of Sound pilot, tracks were processed using the Dolby Atmos Panner plug-in, which was used to automate the three-dimensional panning of various musical elements (Robjohns, Sound On Sound, 2017)[16].

My experience of using the Dolby Atmos plugin tools (see Figure 7 above) at their London studio in August 2017 was an easy adaptation of the knowledge I had gained from the tools I was already using within Ableton. Dolby’s tools tap into a new market of potential users for sound spatialisation. With such commercial tools becoming available, it is clear that spatialisation is a growing compositional element for dance music producers. From discussions I had while at their London studio, Dolby is investing in this technology because they have a vision that it will impact the world of nightclubbing and they want to develop this market in many of the big metropolitan cities around the world. The first Atmos system is in London, the second is installed in Chicago (Sound-Bar), with plans for more (Halcyon in San Francisco, 2018). I was fortunate to try the Dolby Atmos Panner plug-in at their London studio, although for the purpose of this research, I could not use this tool extensively since it is still a private pre-commercial tool in (beta) development.

Spatial thinking about sound plays an important role for Robert Henke (aka Monolake), and his performance ‘Monolake Live 2016’ is a vivid example.[17] It is presented as a multichannel surround sound experience, which Henke has been experimenting with for many years, and includes versions for wave field synthesis[18], ambisonics and other state of the art audio formats.[19] Richie Hawtin (aka Plastikman) has stated that “experimenting in technologies which also work within that field of surround sound, is not only inspiring and challenging but also a good brush up on skills you may need later in life.”[20] (Hawtin, 2005) He has produced a DVD in 5.1 surround sound (DE9: Transitions, 2005 [21]) for a home listening experience. Other music artists like Björk (Vespertine, 2001), Beck (Sea of Change, 2002) and Peter Gabriel (Up, 2002) have all experimented with surround sound releases but spatial audio considerations have not become a key focus of their output. Beyond these artists mentioned above, the use of space, in or out of the studio, has not been used significantly by commercial producers. Whilst this could due to the major record labels having little commercial imperative to promote surround audio formats (SACD, DVD-A, Blu-Ray), more probable is the lack of a single common software/hardware format that allows producers to travel from one venue to the next and setup quickly and efficiently without the need for bespoke hardware requirements.

1.3.3 - SARC - The Sonic Laboratory

Despite the relative lack of commercial interest in spatial music, in experimental sound, space has been an important consideration since the late 1940s. Karlheinz Stockhausen was one of the early pioneers of electronic music to be interested in the spatial distribution of sound both in his electronic and instrumental music. He was interested in space as a parameter in music that could be manipulated just like pitch and rhythm. Stockhausen wrote that: “Pitch can become pulse […] take a sound and spin it, it becomes a pitch rather than its sound” (Stockhausen and Maconie, 1989, p. 93). This presents an extreme form of spatialisation, stemming from a thinking about rhythm and how the parameters can merge into one another. This idea informed Stockhausen works such as Gesang der Jünglinge (1956), Oktophonie (1991),and the Helikopter Quartet (1993). Because of his interest in space, and particularly his performances at the Osaka World Fair in 1970, Stockhausen was invited to open the Sonic Arts Research Centre (SARC), in Belfast on April 22nd 2004. SARC is a world-famous institute for sound spatialisation focused around their spatial laboratory/auditorium which boasts a floating floor with rings of speakers both under and above the audience – an auditorium designed after Stockhausen’s ideas from Musik in Raum (1959).

Figure 8 - The Sonic Laboratory at Queen's University in Belfast, 2005.

Whilst the SARC Laboratory (see Fig. 8) and the 4DSOUND system all offer a unique spatial experience, I am not wanting to work with a bespoke system. What I aim for is a system where I can utilize off-the-shelf software and play and more importantly, perform: a flexible and practical tool to create spatial EDM in a variety of musical space.

1.3.4 - Sound Field Synthesis Methods

Figure 9 - The world's only transportable Wave Field Synthesis system, from ‘The Game Of Life’ (gameoflife.nl), was stationed in Amsterdam for the ‘Focused Sound in Sonic Space’ event in 2011.

Ambisonics and Wave field synthesis (see Fig. 9) are two ways of rendering 3D audio, which both aim at physically reconstructing the soundfield. They derive from distinct theoretical considerations of sound and how it propagates through space. They do slightly different things as they treat sounds in different ways.

Wave Field Synthesis (WFS) allows the composer to create virtual acoustic environments. It emulates nature like wave fronts according to the Huygens-Fresnel principle (and developed by A.J. Berkhout in Holland since 1988) by the assembling of elementary waves, synthesized by a very large number of individually driven loudspeakers. In much the same way that complex sounds can be synthesised by additive synthesis using simple sine tones, so in Wave Field Synthesis a complex wavefront can be constructed by the superimposition of spherical waves. The advantage is that there is a much-enlarged sweet spot. The concept behind WFS is the propagation of sound waves through space and positioning the listener within this environment. It has a precise sound localisation but requires huge number of speakers to prevent spatial aliasing; it is therefore expensive and impractical for my own use.

Ambisonics was pioneered by Michael Gerzon. It quickly gained advocates throughout the 1970s such as David Mallam at the University of York but was never a commercial success. Only recently, since its adoption by Google and the games manufacturer Codemasters has it achieved significant attention. The resurgence of Virtual (Immersive) Reality has seen companies such as Facebook and YouTube adopt spatialisation (3D sound) in their applications in order to provide audio content with a binaural spatial experience.

Ambisonics is a type of 3D spatialisation system that, like WFS and Dolby Atmos, is not speaker dependent, and creates virtual spaces within a speaker environment. The minimum number of channels for a full-sphere soundfield of a fifth-order Ambisonics is 36 channels. They are used to project the spatial information. With the increase of speakers there is an increase in detail in spatial perception. This spatial technique is achieved through manipulating the phase of sound sources rather than through amplitude changes and it can result in a blurring of transients, which is not good for the type of music I make. The lack of transient clarity on kick drum and hi-hat samples has caused me to search for an alternative solution despite the portability of the system.

When assessing different software and hardware systems for spatialisation, and tools for performance I had the following questions in mind:

- Does speaker size found in WFS bring issues for bass resolution for EDM production?

- Does the lack of height (elevated sounds) on the WFS system impact the immersivity that height speakers provide?

- Is my live performance setup, consisting of the Push 2 and the Novation Launchpad control XL instruments, compatible with WFS?

- In Ambisonics are the transients within the soundfield too blurred and not precise enough for low frequency materials found in a kick drum?

My solutions to these questions have shaped my research and technical setup.

1.3.5 - SPIRAL Studio

The studio I have concentrated my research activities in is the SPIRAL (Spatialisation and Interactive Research Laboratory) at the University of Huddersfield. (See Figure 10 below)

Figure 10 - SPIRAL Studio at the University of Huddersfield, 2015.

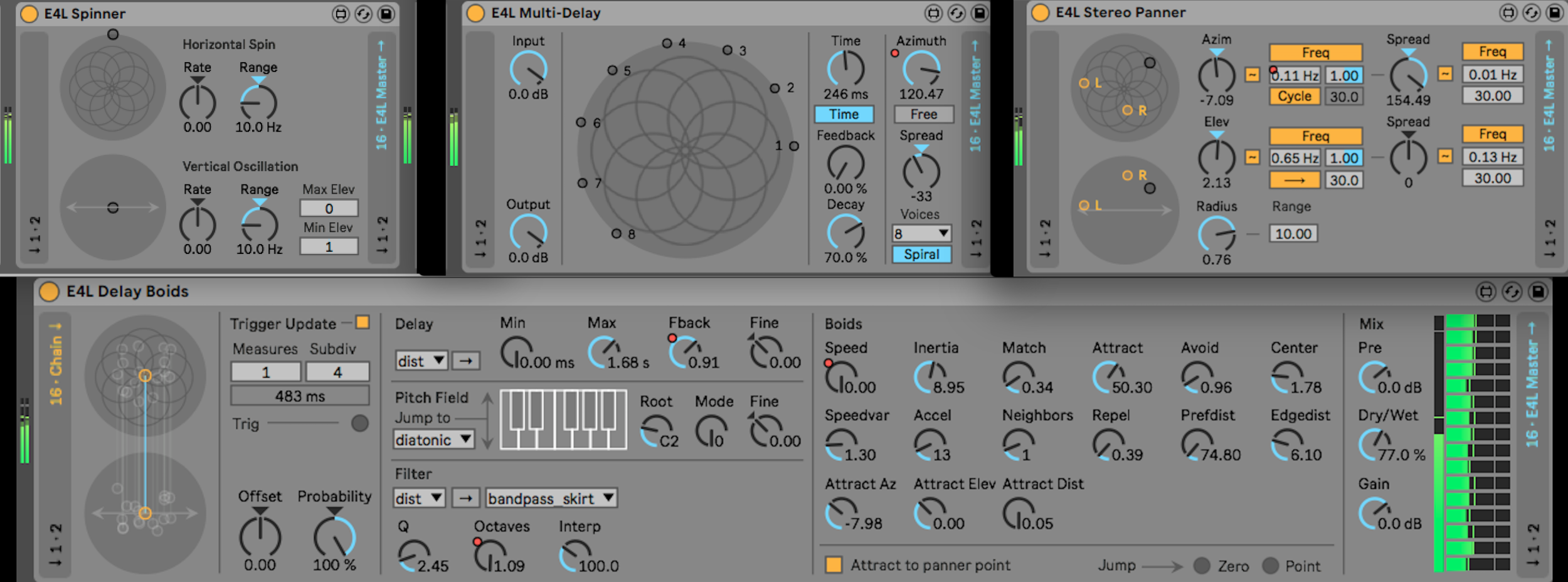

My research has facilitated new ways for me to compose music and has developed my approach to spatialising sounds in the SPIRAL Studio. In order to compose and perform live within an immersive listening environment, I have explored many tools but settled on Ableton Live[22], in conjunction with the Push 2 and Novation’s Launchpad control XL (see Figure 11 below), using Max4Live spatialisation objects. This integrated performance and compositional setup has enabled me to create EDM with a sense of sound envelopment using a system comprising 24 channels on three octophonic rings of speakers. From a compositional perspective, the SPIRAL, drawing on Brümmer’s insights mentioned earlier, allows me more perceptual freedom to add more layers to my music compared to the clustered traditional stereo approach to sound.

Figure 11 - Ableton Push 2 and Novation’s Launchpad control XL, 2017.

Concerning the earnest attention given to space by acousmatic composers, I concur with Brümmer’s findings in his article New developments for spatial music in the context of the ZKM Klangdom: A review of technologies and recent productions, where he states that:

The musical potential of spatiality is only beginning to unfold. The ability to listen consciously to and make use of space will continue to be developed in the future, larger installations will become more flexible and more readily available overall, and the capabilities of the parameter space will be further explored through research and artistic practice. This will make it easier for composers and event organisers to stimulate and challenge the audience’s capacity for experience, as the introduction of the recently introduced object-based Dolby Atmos standard indicates. But composers will also find more refined techniques and aesthetics that will take advantage of the full power of spatial distribution. If this happens the audience will follow, looking for new excitements in the perception of sound and music (Brümmer, 2016, p. 18).

Ultimately, my aim in this research has been to bring together real time spatialisation and live composition. Gerald Bennett (Department Head at the Institut de Recherche et Coordination Acoustique/Musique (IRCAM) in Paris from 1976-1981 and Director of the Institute for Computer Music and Sound Technology at the Hochschule Musik und Theater, Zurich from 2005-2007) noted that, “finding a balance between spatialisation and the restriction of interpretation in performance is difficult” (Bennett, 1997, p. 2). I want, as much as possible, to create and plan my compositional spatial movement in the studio but to be able to intervene in the spatial trajectories assigned to sounds during my performance. When working in the studio, I noticed that when I use more than two channels (stereo), the additional speakers allow my sounds to ‘breathe’ and facilitates a spatial counterpoint that generates musical relationships or dialogues between them. Sometimes, the clustering of sound materials grouped together within a stereo file can lead to sounds masking each other that would do so when presented over large multi-channel systems. This is not merely a matter of mixing skill within the stereo field, but rather about the spreading or separation of frequency content within a 3D space to create a sense of immersion and viscerality that is not possible within the stereo field. Thus, by having spectral divisions in my sounds, what I call ‘gravitational spatialisation’, it helps me to achieve the immersive quality that I want the audience to experience no matter where they are situated within the performance space.

1.4. - Composition and spatialisation tools

The SPIRAL Studio is a 25.4 channel studio. It comprises three octophonic circles of speakers that provide a height dimension, a central high speaker pointing straight down to the sweet spot, and four subwoofers. Within Ableton Live I experimented with several software tools that enable spatialisation.

The Spatial Immersion Research Group (GRIS) at the University of Montreal developed the OctoGRIS[23] and SpatGRIS (Audio Unit plugins for controlling sounds over speakers) allows the latter plugin up to 128 outputs and includes a height dimension and was released towards the end of this research project in March 2018). The OctoGRIS allows the user to control a live spatialisation on a dome from within an audio sequencer. Considering the number of spatial gestures that I wanted to include with several audio loops, the plugin used too much CPU. Therefore, I had to find an alternative, less CPU intensive solution.

Another tool that I tested was MNTN (The Sound of the Mountain)[24]. This software allows the user to design immersive listening experiences with a flexible, lightweight, and easy-to-use graphic user interface (GUI) for spatial sound design. With it, the user can play the space as an instrument. MNTN (see Figure 12 below) enables the user to perform spatial concerts with real 3D sound, and with as many loudspeakers as is desired. As I developed and built my performance setup with Ableton’s software, I selected a tool already integrated within the plugins of Live since I was more interested in the aesthetic application of these tools rather than their technical implementation.

Figure 12 - MNTN, the software was developed with the idea of enabling the production of immersive sound, 2017.

I have used the Dolby Atmos plugin in their studio (with the Rendering Master Unit – RMU). It was easily adaptable for the software I am already using: Ableton Live. Dolby is developing a plugin to be used within popular DAWs, for the user to integrate the spatialisation dimension into their work but it is unfortunately not yet commercially available to dance music producers and the general public.

1.4.1 - How do software and hardware tools affect my workflow

My goal is to bring aspects of my past acousmatic practice into dance music in order to create immersive and visceral sound environments that are still novel and relatively uncommon. I am not claiming that I am developing new sound synthesis or new sound processing techniques, nor any new sound spatialisation techniques, it is rather about the integration of and application of these ideas in to my compositional practice. Even though there are many other spatialisation techniques that I could have used throughout my research and could have developed far more sophisticated directional or structural sound trajectories and gestures, the desire to work and mix live has shaped the tools I have chosen to work with. The concept of performing a spatial music is fundamental for me. This extends far beyond sound diffusion – a practice common in acousmatic music – and more towards the concept of ‘real-time composition’.

I decided not to use a MAX patch with SPAT to create sound trajectories, which though perhaps more sophisticated and controllable in the studio, caused CPU issues when used in real-time with multiple instantiations as plug-ins on separate tracks. I have aimed to use and adopt standardized tools in order to optimize their potential and create something that is highly flexible and easily transferable from one system to another without having to install additional software tools. Whilst I acknowledge that my technical setup has allowed me to do achieve my research objectives, I also acknowledge that the system has its limits – ones that I would like to transcend as my practice continues to develop. I have used all of Live’s sends features to explore its potential as a real-time spatialisation tool. In this respect, my research has been highly successful as I have been able to create up to two-hour live sets of 24.4 channel EDM on my live steaming YouTube channel.

1.5 - Spatialisation and EDM: My setup

When performing my work, I aim to create an immersive and visceral flow of sound that carries the listener like an ever-moving wave. Immersion in that musical flow is more important than the musical dynamic or listening to the gestural dynamic, because it is more about feeling and absorbing the music rather than appreciating key changes or a specific sound. “Low-frequency beats can produce a sense of material presence and fullness, which can also serve to engender a sense of connection and cohesion” (Garcia, 2015). It is the effect that becomes more important rather than the music itself, and because there are not many contrasting musical sections, the listener can become immersed in it. Rupert Till in his article Lost in Music: Pop Cults and New Religious Movements, writes:

In most traditional societies, Western European culture being a notable exception, musical activity is a social or group-based activity, and is associated with the achievement of altered states of consciousness. […] Music has the power to exert enormous influence on the human mind, especially when people are gathered in groups, and the euphoric power of group dynamics is brought into play (Till, 2010, p. 12).

In my work, I intend the audience to achieve such altered state of consciousness, to offer them a musical journey into the Kantian sublime. Also, I am interested that the audience perceives the movement of the sounds in space rather than paying attention to the specific trajectory of sounds that creates a space within where they are situated. The way I create a sense of immersion and viscerality in my music is not just about volume, rhythm, repetition, but it is how I handle the music material, through long emerging textures. These textures accumulate through the sense of musical flow rather than discreet blocks of sounds.

What I intend with my spatialisation research is to provide an enhanced experience of EDM. In my opinion, spatialisation is not just structurally or compositionally significant; it enhances the nightclub experience through creating a sense of immersivity with the distinct visceral quality arising from the enveloping of the club-goers with music in a particular space. It is this experimental sensation of immersivity that drives my spatial thinking rather than abstract concepts.

The method I have used to spatialise my sounds allows me to perform on a sound system that can have up to 24 speakers. Most sound systems I have come across have less speakers than this, thus I can adapt my Ableton sessions to a multitude of speaker setups and presentation formats. The Max4Live plugins “Max Api Ctrl1LFO” and the “Max Api SendsXnodes” provide spatialisation easily and intuitively (see Figure 13 below).

Figure 13 - Max4Live spatialisation tool for multichannel diffusion, 2017.

This pair of plugins allows the user to send audio to 1 or to 24 channels at the time. The selection of numbers of speakers can vary and can be modified throughout the composition process. My technique was influenced by the position of the three rings of speakers at different height in the SPIRAL Studio. In keeping with my concept of ‘gravitational spatialisation’, I decided to keep most of my loops containing ‘heavy’ low frequencies on the bottom circle of eight speakers while moving or positioning the mid and high frequencies on the two rings of speakers above. This creates a ‘gravitational spatialisation’ where higher pitch sounds are usually heard above the lower bass sounds or kick. Since the ears perceive and localise the high pitch sound more easily (Lee, 2014), I tend to place the sounds on the higher rings of speaker. This last finding is supported by Hyunkook Lee’s article Psychoacoustic Considerations in Surround Sound with Height, where he states that: “The addition of height channels in new reproduction formats such as Auro-3D, Dolby Atmos and 22.2, etc. enhances the perceived spatial impression in reproduction” (Lee, 2014, p. 1).

When composing music with space as a musical parameter, there are spatial compositional techniques that we can take into consideration, as outlined by acousmatic composer Natasha Barrett:

Common compositional techniques encompass the following:

-Creating trajectories; these trajectories will introduce choreography of sounds into the piece, and this choreography needs to have a certain meaning.

-Using location as a serial parameter (e.g. Stockhausen); this will also introduce choreography of sounds.